I teach controversial subjects–those topics that most people are told to not discuss if you wish to be invited to holidays. In philosophy and religious studies courses we discuss the gambit of subjects that are inclined to get you uninvited to next year’s family festivities. Abortion? Yep. Politics, God’s existence, euthanasia, sex, race, drugs, and climate change? Those are discussed as well.

Of course we also discuss more *tame* subjects like the meaning of life, the nature of truth, beauty, reality, and knowledge. But even when discussing these issues, students are asked and encouraged to reflect upon their core values–those values that have been shaped by either their families or communities. So, even with these more abstract issues a student is bound to (and should) experience some level of cognitive dissonance.

The risk involved in these discussions is that a student may end up rejecting his or her own personal views, which are also the views of the community with which the student self-identifies. This can be an unnerving process and I’ve seen students have mental breakdowns, be shunned by their own families, and, yes, not invited to holidays.

A quick example is when I’ve taught environmental ethics and a student ended up becoming a vegetarian as a result of the class discussion (this is not a view that I force upon students, but just have them explore). As a result of the student’s newfound vegetarianism, the student was no longer invited to the holiday dinner–which comprised of a flesh-based meal.

I’ve observed that when students become aware of these social risks by seriously taking on the intellectual challenge of assessing their own beliefs that they are reticent to engage the material in an honest way. I have also seen students who become frustrated that they have a tendency to shut down or even avoid class altogether. In fact, just yesterday, I had a student stop by my office to tell me she dreads coming to my class. She explained that she thoroughly enjoys my teaching and the class itself is not so bad, but that she could not bring herself to come to the class meeting. Interestingly, the topic we were discussing in class was on the meaning of life. I encouraged and invited her to come to class even though she felt that way, but she was committed to not attending.

So, what sort of management issues must I face in a philosophy or religious studies course? What I’ve found is that students are potentially triggered (to use millennial-speak) by the course content. (Students using a cellphone or laptop in my classes is no longer an issue–I can share the ways I’ve dealt with that). This is a problem for philosophy classes across the country. In fact, I’m facilitating a panel at the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division meeting on this very issue:

https://www.apaonline.org/page/TeachingHub2020CFP#facilitating

Simply because the materials I teach are potentially troublesome or triggering to students does not mean that I avoid the topics. The world is both troublesome and triggering. Classrooms are an opportunity to prepare students for the world. Therefore, we (as instructors) must assist students be prepared to navigate a troublesome world. So, I refuse to shy away from or not teach something simply because it is potentially upsetting to students.

In handling potentially triggering and contentious materials, there are a couple approaches I’ve adopted. First, I explain to them that philosophy offers tools of analysis that allows them to see different perspectives of an issue (again, critical thinking…not just using it, but teaching it).

I typically begin with Aristotle’s quote: “it is the mark of an educated person to search for the same kind of clarity in each topic to the extent that the nature of the matter accepts it…Each person judges well what they know and is thus a good critic of those things. For each thing in specific, someone must be educated; to one must be educated about everything” (Nicomachean Ethics, 1 1094a24-1095a).

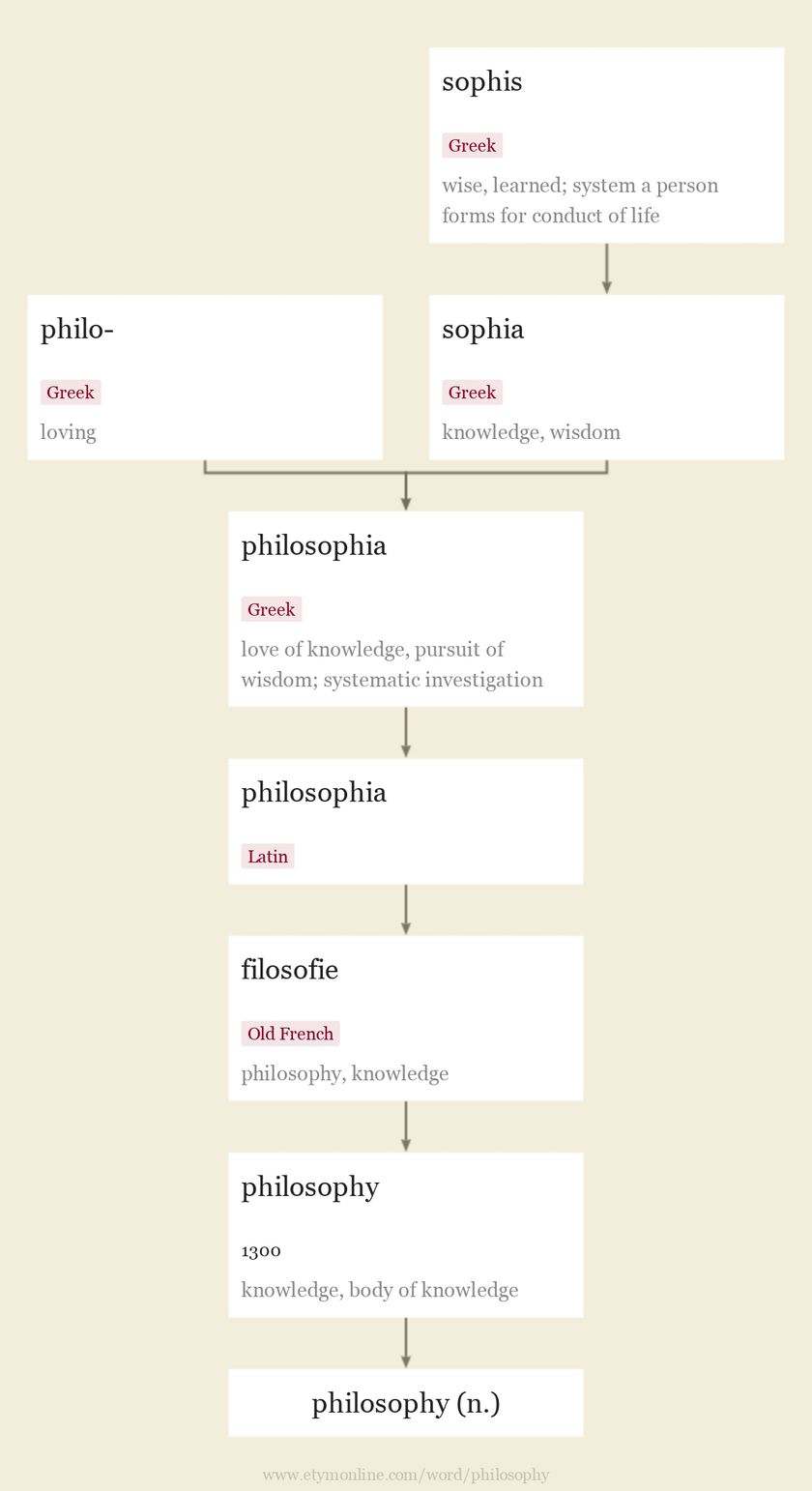

The point of this quote being that students, in becoming educated persons, must become as clear as possible on a topic that they are wanting to discuss. Before they begin judging, critiquing, or assessing the topic being discussed they must first inform themselves about the topic to the best of their ability.

Now many students certainly believe that they are already in a well-informed position to determine the truth of a claim, but a quick round of Socratic inquiry reveals to students that they don’t really understand what they are discussing. For example, the question “What is the meaning of life?” seems to have a easy answer, but as soon as we dig in a little and ask “What do you mean by ‘meaning’?” Students are stuck–is it value, is it utility, is it function, is it purpose? Also, what sort of meaning is the right kind of meaning for evaluating whether or not someone does in fact live a meaningful life.

This is a helpful step to allowing students to at least be receptive to the idea that they do not know what the meaning of life happens to be. Yet, they seem to want to live meaningful lives, so how do we sufficiently answer the question?

This first step assists students to at least distance themselves from their own preconceived notions of what constitutes a meaningful life, which allows me to begin discussing the various theories on the meaning of life. By students realizing that they do not have a well-informed stance on the matter, they do not feel that their own personal views are being attacked. Instead, we get to treat the different theories as independent objects that can be dissected and evaluated.

The second step is tied to issues that may be more immediately triggering. In particular, in my medical ethics courses I discuss moral issues surrounding procreation, including abortion. This is particularly a touchy topic given the politicalization of the issue and the fact that many students may either have or know someone who has had an abortion. I do not ask students to share their own experiences and I do not even have them share their own views on abortion. Instead, I expose them to how philosophers have discussed the issue and have students assess those arguments. In particular, I include a debate held between Peter Singer and Don Marquis who take opposing positions on the issue.

The benefit of this approach is that students are able to see how we can discuss very contentious issues without having to throw chairs at one another or get emotionally heated. So, this is a good way to model the kind of discussions that students should be having when dealing with things that may lead them to become upset. Furthermore, I don’t have students discuss which person they agree with most, but, instead, I have students analyze the different arguments (using tools provided in creative thinking and logic courses). I then have students discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each argument. The benefit is that students begin reflecting on their own beliefs and assess what their own reasons may be for holding onto one position as opposed to others.

Overall, students will have to face difficult subjects. We have a responsibility to assist students cultivate the right set of tools for thinking about challenging materials without resulting in them being triggered. Sure, sometimes triggering can’t be avoided, but such is life…the world does not provide trigger warnings. By having students learn how to emotionally distance themselves from contentious topics and analyze them in a more concerted way will ensure that students are better able to think about the things that impact their own lives. Yes, this also includes thinking about the meaning of life.